810 AD to 830 AD, Psalm 88: Agobard.

This site was first built in French (see www.147thgeneration.net). The English translation was mainly done using « google translation ». We have tried to correct the result of this translation to avoid interpretation errors. However, it is likely that there are unsatisfactory translations, do not hesitate to communicate them to us for correction.

(for that click on this paragraph)

Summary

This generation is from the years 810 AD to 830 AD.

According to our count, this generation is the 88th generation associated with Psalm 88. It is in this Psalm 88 that we therefore find an illustration of the facts of this generation.

The Abbasid war of succession on the death of Haroun El Rachid turns in favor of Al Ma’mûn, favorable to innovative thought movements, marked by foreign influences and legacies. His defeated brother Al Amin was a supporter of traditionalism. His victory probably contributed to initiate the golden age of the Abbassids by rediscovering the treasures of antiquity.

The Abbasid example is also followed by the Umayyads of Spain. Al Hakam’s reign is one of terror; however, he left his successor, Abd Al Rahman II, a stable empire. He is a great ruler who now rules Al-Andalus and gives birth to a great civilization.

The Muslim world is changing on both sides of the Mediterranean and embodies the civilized world for many centuries.

The Christian world, especially incarnated in the new empire of the West if it is still favorable to the Jews suggests a harmful evolution by the emergence of a hostile clergy who will eventually win the following generations which will result in to drive the West into obscurantism.

Louis Le Pieux (the Pious) succeeds his father Charlemagne. Like all Carolingian kings, Louis Le Pieux has a rather benevolent policy towards the Jews but his protection is not enough to durably stem the anti-Jewish positions of his clergy he reinforces.

The bishops, taking advantage of their new statutes, react to the king’s “laxity” towards the Jews. Among them, Agobard de Lyon, who knows Judaism perfectly. Despite the mistrust of power, he continues his fight against the “Jewish threat”. He had undertaken missionary work with the Jews of Lyons, at the same time as with those of Chalon and Macon. The Jews try to scare their children away, Agobard manages to convert nearly 50 of them.

The emperor opposes Agobard’s action, but the fact that the conversion took place in a church will not allow him to intervene. Agobard, in his fight against the Jews, even tries to rally the children of Louis the Pious against him. This leads to his dismissal and exile in Italy.

This does not prevent the undermining work of Agobard from bearing fruit. The battle of Agobard, which only recalls that of the Visigoth kings of Spain, continues to sow the hatred of the Jew on Christian soil. When this hatred is ripe it will hit the Jews hard on many occasions, largely justifying the term “valley of weeping” in Christian Europe.

Talk

The Muslim world embodies the civilized world

At the level of the Abbasids, this generation is that of Caliph Al Ma’mûn (813-833) who succeeds Al Amin (809-813). Haroun El Rachid had in fact planned his succession between his two sons Al Amin and Al Ma’mûn, but when he died in 809, the two brothers clashed. Al Amin, who had tried to drive his brother away, was defeated in 813. Al Ma’mûn besieged Baghdad, which was taken and destroyed in 813 after fierce resistance. In fact, behind the fratricidal struggle, there is also a cultural struggle:

- The personal rivalry [1] between the two brothers – one of whom, al-Ma’mun, was unquestionably superior in intelligence – only reflected a deeper opposition. That of the politico-religious tendencies that had begun to confront each other during the reign of Haroun and for which each of them had taken sides. Al-Amin relying on traditionalism and Arab culture, al Ma’mûn being in favor of innovative thought movements, marked by influences and foreign legacies that were particularly in favor of the populations of the eastern provinces.

These choices probably contributed to initiate the golden age of the Abbassids by rediscovering the treasures of antiquity.

The Abbasid example is also followed by the Umayyads of Spain.

This generation, for the Umayyads, is marked by the reign of Abd Al Rahman II (822-852) who succeeds Al Hakam I (796-822). The reign of Al Hakam is under the sign of terror, all rebellion is severely repressed. But thanks to this iron fist, Al Hakam leaves to his successor an empire (the essential of Spain amputated from the northern territories in the hands of the Christians) stable, as he himself indicates to his son shortly before his death.

Al-Andalus [2] is now ready to be ruled by a great ruler and to give birth to a great civilization. This great ruler is Abd Al Rahman II.

The Muslim world is changing on both sides of the Mediterranean and embodies the civilized world for many centuries. The Christian world, especially incarnated in the new empire of the West if it is still favorable to the Jews suggests a harmful evolution by the emergence of a hostile clergy who will eventually win the following generations which will result in to drive the West into obscurantism.

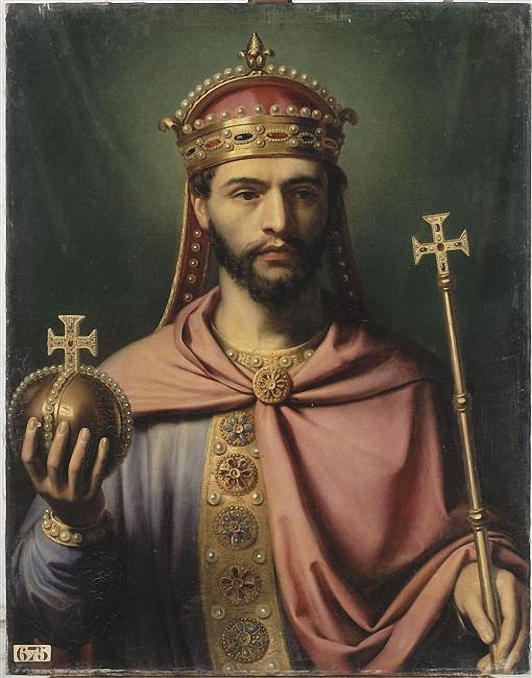

Louis Le Pieux (the Pious)

During this generation, it is Louis Le Pieux (the Pious) (814-840) who succeeds his father Charlemagne. Like all Carolingian kings, Louis Le Pieux has a rather benevolent policy towards the Jews but his protection is not enough to durably stem the anti-Jewish positions of his clergy he reinforces.

The Carolingian kings needed the Jews and their commercial activity to emerge the new empire, the protection provided mainly to preserve this essential wheel of the economy. This is why the laws aiming to make them play indirectly a role of treasurer of the kingdom: the Jews can not profit from their wealth which only serves the interests of the kingdom.

Louis the Pious is a man of deep faith, he reinforces the role of the church in the state. Rich in the apparent protection of power, the Jews are even followers of Christian elites.

The clergy offensive

The bishops, taking advantage of their new statutes, react to the king’s « laxity » towards the Jews and thus lay the foundations for an anti-Jewish policy that will remain in the Christian West for many centuries. Even until today.

As is unfortunately the case in the long history of the cohabitation of the Jews on Christian soil, the one who stands against them, Agobard of Lyon, knows Judaism perfectly.

As a perfect connoisseur of the Jewish world, he realizes the danger for the Christian faith that can be too permissive cohabitation.

Despite the mistrust of power, he continues his fight against the « Jewish threat »:

- Without [3] even any artifice, the thing (the only choice left to the Jews must be conversion or exile) is confessed by Agobard, between 816 and 822-825, in his letter to Louis the Pious. He had undertaken missionary work with the Jews of Lyons, at the same time as with those of Chalon and Macon. The success was particularly strengthened by the fact that, « all Sabbaths, the word of God was preached in the synagogues by our brothers and priests ».

- After these sermons inflicted on the Jews in their own synagogues – a remarkable innovation – they try to smuggle their children away, because it is on them especially that the missionary zeal of the fiery bishop is exercised. Agobard organizes a meeting of all the young people still on the spot, and this time in the Church. A new exhortation results in first six, then another forty-seven young people ask for baptism.

Agobard’s fight

The emperor opposes Agobard’s action, but the fact that the conversion took place in a church will not allow him to intervene. Agobard, in his fight against the Jews, even tries to rally the children of Louis the Pious against him. This leads to his dismissal and exile in Italy.

This does not prevent the undermining work of Agobard from bearing fruit.

His successor, Amolon, continues the fight against the Jews. The small glimmer of hope brought by the accommodative policy of the Carolingian kings to the Jews has been short-lived, the fate of the Jews on Christian soil in the coming generations and centuries will be much duller and in some dramatic cases.

The content of this psalm is thus naturally linked to the generation that interests us but also with a projection of these events on future generations. Thus the psalmist does not fail to illustrate this generation by recalling the past suffering of the Jewish people during the first generations of the night, during which he almost disappeared several times:

- A song with musical accompaniment of the sons of Korah, for the conductor, about the sick and afflicted one, a maskil of Heman the Ezrahite.

- O Lord, the God of my salvation! I cried by day; at night I was opposite You.

- May my prayer come before You; extend Your ear to my supplication.

- For my soul is sated with troubles, and my life has reached the grave.

- I was counted with those who descend into the Pit; I was like a man without strength.

- I am considered among the dead who are free, as the slain who lie in the grave, whom You no longer remember and who were cut off by Your hand.

In fact, the generation that interests us is rather propitious to the Jews. The Arab world is tolerant and open to knowledge, the Christian emperor of the West protects the Jews effectively and especially prevents his Bishop Agobard from being too harmful to the Jews. But the psalmist has a broader vision than the present generation and knows that the relative calm of this generation is presage of darker times for the future.

Because in the past also the Jews have known periods of lull but always followed by darker periods. The image held by the editor of the psalm is telling, indeed in the following, it evokes the waves. Between two waves, one can feel relieved and try to regain his strength after suffering the previous wave, but that does not prevent to undergo the next wave before experiencing a new respite and so on.

This is what the continuation of the psalm expresses:

- You have put me into the lowest pit, into dark places, into depths.

- Your wrath lies hard upon me, and [with] all Your waves You have afflicted [me] constantly.

To illustrate this speech, the sequel to the Psalm evokes the most harmful (short-term) action of Agobard who attack the children of the Jews of Lyon who by converting to Christianity end up denigrating their own. Trapped in the church, there was no salvation for them, no way to escape.

This is the story of the following verses of the psalm:

- You have estranged my friends from me; You have made me an abomination to them; [I am] imprisoned and cannot go out.

But this unfortunate fact is only the tip of the iceberg. The battle of Agobard, which only recalls that of the Visigoth kings of Spain, continues to sow the hatred of the Jew on Christian soil.

When this hatred is ripe it will hit the Jews hard on many occasions, largely justifying the term « valley of weeping » in Christian Europe.

It is because it has the faculty to see by vision what awaits the Jewish people that the psalmist can in the rest of the psalm describe the consequences of hate speech emitted during this generation. Speeches that do not worry, presumably beyond measure the Jews of this generation but will have terrible consequences on future generations.

This is what the rest of the psalm describes:

- My eye has failed because of affliction; I have called You every day, I have spread out my palms to You.

- Will You perform a wonder for the dead? Will the shades rise and thank You forever?

- Will Your kindness be told in the grave, Your faith in destruction?

- Will Your wonder be known in the darkness, or Your righteousness in the land of oblivion?

- As for me, O Lord, I have cried out to You, and in the morning my prayer comes before You.

- Why, O Lord, do You abandon my soul, do You hide Your countenance from me?

- I am poor, and close to sudden death; I have borne Your fear, it is well-founded.

Finally, the psalm concludes by connecting the future fate of the Jews to their fate by recalling this notion of waves (waves) and bringing it closer to the facts proper of the generation (my intimates are invisible):

- Your fires of wrath have passed over me; Your terrors have cut me off.

- They surround me like water all the day; they encompass me together.

- You have estranged from me lover and friend; my acquaintances are in a place of darkness.

[1] Janine Sourdel and Dominique Sourdel: « Historical Dictionary of Islam ». Heading al Ma’mûn (French: « Dictionnaire historique de l’Islam ». Rubrique al Ma’mûn (p. 529, 530) ).

[2] Conclusion by André Clot (« Muslim Spain », Chapter: « The Umayyad Emirs », page 66) following the preceding quotation. (French: « L’Espagne musulmane ». Chapitre : « Les émirs Omeyyades » p. 66) ).

[3] Bernhard Blumenkranz: « Jews and Christians in the western world 430-1096 ». Chapter III: « The Intellectual Encounter » (French: « Juifs et Chrétiens dans le monde occidental 430-1096 ». Chapitre III : « La rencontre intellectuelle » (p. 94) ).