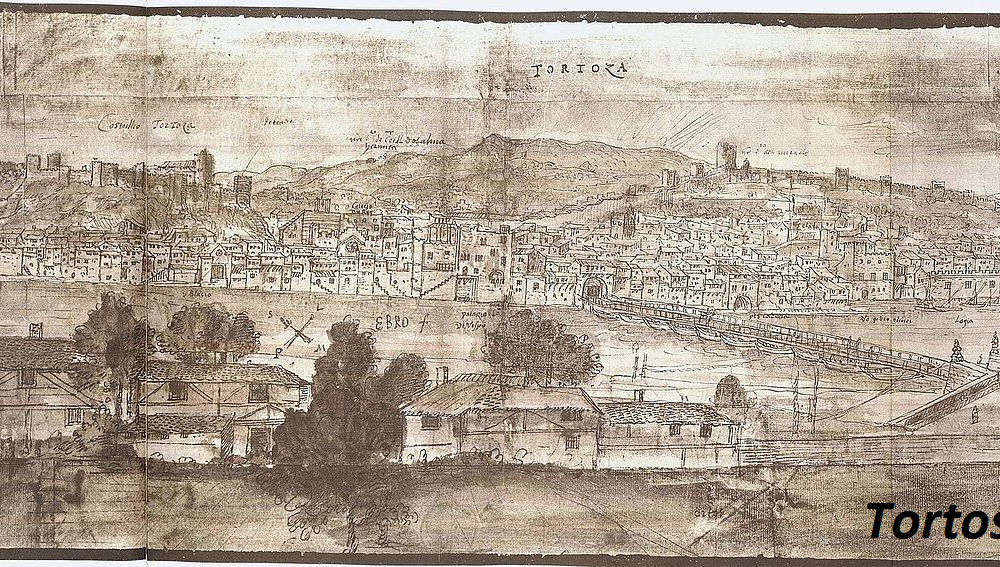

1410 AD to 1430 AD, Psalm 118: Tortosa.

This site was first built in French (see www.147thgeneration.net). The English translation was mainly done using « google translation ». We have tried to correct the result of this translation to avoid interpretation errors. However, it is likely that there are unsatisfactory translations, do not hesitate to communicate them to us for correction.

(for that click on this paragraph)

Summary

This generation of the 1410s and 1430s.

According to our count, this generation is the 118th generation associated with Psalm 118. It is in this Psalm 118 that we therefore find an illustration of the facts of this generation.

The Turkish Empire was at its peak when it decided in 1683 to attack Vienna and fail. It is the end of the European dream for the Ottoman Empire. France appears to be at its peak under the reign of Louis XIV, but the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the war against Holland in 1672 will be all obstacles to its hegemony in Europe. A new revolution takes place in In the previous century, and in the wake of the massacres of the First Crusade of 1096, the Jews feared mainly for their lives and unfortunately with good reason. This generation marks a new strategy on the part of Christianity towards the Jews: conversion or a life of an outcast locked in ghettos.

The situation of the Jews in Christian Spain, mainly in the Kingdoms of Castile, therefore worsens in this generation, even if the threats are no longer really of a vital nature. Many Jews from the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon find refuge in the Muslim kingdom of Granada as well as the Christian kingdoms of Portugal or Navarre. The reception of the Kingdoms of Navarre and Portugal must be put into perspective, these kingdoms then having a serious population deficit. At the end of the 15th century when these demographic problems will have disappeared, the situation of the Jews of these kingdoms will develop negatively.

Many Jews who have succumbed to Christianity make it their duty to fight against their former co-religionists. This is particularly the case with Joshua Ha-Lorki. Under his new convert name, Geronimo de Santa Fé, he organized the Tortosa dispute.

However, the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula have toughened up and the Tortosa dispute does not have the desired results. She may even succeed in uniting and rebuilding a community that had been battered by the events of 1391. During the dispute, the Pope and his acolytes failed to shake in their faith any of the twenty-two representatives of Judaism.

While chatting in Tortosa, Vincent Ferrer continues his proselytizing campaign with the help of his troop of flagellants. Under the action of the terror they inspired and the fiery speeches of the Dominican, thousands of Jews were baptized (February – June 1414). These new converts, the papal court made them come in groups to Tortosa, where they publicly made their profession of faith as Christians. But the Pope was disappointed in his forecasts, the Jews did not convert. Apart from a few shortcomings, the large communities of Aragon and Catalonia remained steadfast in their faith.

In Portugal, the Jews did not have to suffer from Ferrer’s fanaticism. Thanks to the king’s tolerance, the Jews of Portugal enjoyed complete security, and many baptized Jews from Spain took refuge in this country.

In the midst of their worries, the Jews suddenly saw a ray of hope shining for them. The Council of Constance had indeed just elected Martin V. This one will prohibit the baptism of the Jews by constraint, the disturbance of their worship or to put obstacle to their commercial relations with the Christians.

In fact, the successive attacks by Christians on the Iberian Jewish communities have resulted in numerous conversions. At first, many of them were sincere and corresponded to an aspiration of some to finally belong to the new Spanish people which had been created for several generations as the reconquest progressed. Still others considered that Christianity was ultimately just an extension of Judaism which was not incompatible with it. Most converted mainly in the hope of avoiding segregation measures but remained deeply Jewish at heart.

The episode of 1391 enabled Sephardic Jews to be more ideologically offensive. While this will not save their communities decades later within the Iberian Peninsula, this fighting spirit will allow Sephardic Judaism to survive the expulsion of 1492 from Spain and Portugal. The reaction of Jewish intellectuals upstream of this generation to the Christian cultural offensive enabled the Jews of this generation, and as we will see in 1492, a significant number of Jews to prefer exile to abandon their faith.

Talk

A new century

This generation closes the fourteenth century, which was a century of massacres during which the Jewish people almost disappeared several times. The century that opens has many other pitfalls for the Jewish people, but not in terms of massacres. It will come later.

This is why the psalmist, at the beginning of this psalm, thanks the Lord for allowing the Jewish people to survive this century of misfortune:

- Give thanks to the Lord because He is good, for His kindness is eternal.

- Israel shall now say, « For His kindness is eternal. »

- The house of Aaron shall now say, « For His kindness is eternal. »

- Those who fear the Lord shall now say, « For His kindness is eternal. »

- From the straits I called God; God answered me with a vast expanse.

The conclusion « God answered me with a vast expanse » of this passage is justified by the many exoduses that Jews were forced to practice to protect themselves from persecution. The thriving communities of Europe (France, Germany) have been replaced by new communities further east, in Poland and Lithuania, and in other lands that the Jews did not imagine existed at the beginning of their exile in the destruction of the second temple. This inexorable exodus through the nations will not stop and will continue until the final return to the land of Israel.

In the previous century, and in line with the massacres of the first crusade of 1096, Jews feared primarily for their lives and unfortunately rightly so. This generation marks a new strategy on the part of Christianity towards the Jews: conversion or a pariah’s life locked in ghettos. The situation of the Jews in Christian Spain, mainly in the Kingdoms of Castile, the most important of the four Christian kingdoms of Spain, already precarious in previous decades worsens to this generation, even if the threats are no longer really order vital.

The situation of the Jews in the kingdom of Aragon is also deteriorating, having already undergone the events of 1391, the Jews of this kingdom will be in first line to undergo the effects of the dispute of Tortosa (1413-1414). This despite a measured attitude of the Aragonese crown.

Many Jews from the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon find refuge in the Muslim kingdom of Granada as well as the Christian kingdoms of Portugal or Navarre.

However [1] the reception of the Kingdom of Navarre must be relativized because this kingdom saw its population decrease from 100,000 inhabitants in the early fourteenth century to 30,000 in 1430, in this context any human contribution is welcome. The Kingdom of Portugal is also experiencing a demographic deficit during this period. At the end of the fifteenth century when these demographic problems disappeared, the situation of the Jews of these kingdoms will evolve negatively.

For the main kingdoms of Spain, abuses against Jews will have direct or indirect consequences for their future in the Iberian Peninsula.

While Sephardic Judaism (« Spanish ») is living its last years in its sphere of origin (Spain) while preparing for the next exile, the long-term degradation of Jewish communities in Western Europe (England, France and Germany), yet once so promising, continues to the present generation especially in Germany.

This will continue to succeeding generations thus configuring Ashkenazi (« German ») Judaism for its survival also outside its sphere of birth (the « great » Germany encompassing a large part of present-day France). The Jews who stay in Germany, leave the big cities to shelter in the villages and small towns.

The critical situation in which Sephardic Judaism finds itself, which seems to thus join the fate of German and French Judaism, is thus evoked in the following of the psalm of this generation:

- The Lord is for me; I shall not fear. What can man do to me?

- The Lord is for me with my helpers, and I shall see [revenge] in my enemies.

- It is better to take shelter in the Lord than to trust in man.

- It is better to take shelter in the Lord than to trust in princes.

But this passage at the same time as it evokes the mistrust of nations towards the people of Israel also gives a sign of hope. No matter how much the nations devote themselves to the people of Israel, Israel will continue to seek their ultimate salvation from the Lord.

This diagnosis explains why Sephardic Judaism will succeed in surviving two centuries of continuous attacks, the Fourteenth Century with its massacres and the Fifteenth Century with massive attempts at conversion.

Tortosa’s dispute

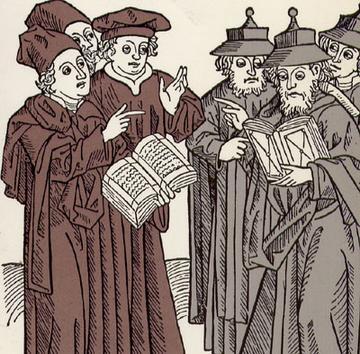

We saw in the previous generation how doubt could penetrate even the most hardened Jews in the image of Joshua Ha-Lorki who questioned Salomon Ha-Levi his former teacher to think now converted under the name of Pablo Santa Maria.

Ha-Lorki meanwhile also succumbed to the sirens of Christianity and adopts his new name of convert Santa Fe Geronimo (Hyeronymus of Sancta Fide). It is with this new name, and like many converts before him or after him, that he will make a point of fighting his old co-religionists:

- (Two decades after 1391, with its new convictions) ha-Lorki [2] tried to organize a public dispute in Alcaniz. But this debate, which initially seemed to be only a modest thing, was transformed into a major confrontation between the representatives of the Jewish communities of Aragon and the Christians led by ha-Lorki. The pope himself sent letters to each of the Jewish communities asking them to send their best scholars to the papal court in Tortosa to take part in this debate. For the Jews of Aragon, who had not yet recovered from the riots of 1391 and the wave of conversions (either by force or choice) that ensued, the moment could not have been more poorly chosen. They were well aware that the dispute was staged to encourage even more members of their people to convert.

- And what splendor! When the Jews arrived at the papal court on February 7, 1413, for the official opening of the dispute, they found in the big court 70 seats occupied by cardinals, bishops and archbishops all dressed in their finery. The audience, which numbered nearly a thousand, was composed of eminent members of the papal court, the local nobility, and the municipality; intellectuals and Jewish political leaders from all over the kingdom of Aragon were also present.

- The method used by the Christian and Jewish debaters had not changed since 1263, when Pablo Christiani confronted Nahmanide. Unlike the Barcelona dispute, however, it dragged on for months.

However, the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula had hardened and the dispute of Tortosa did not have the expected results. She may even succeed in rebuilding and rebuilding a community that had been mistreated by the events of 1391:

- Jealous [3], undoubtedly, the success of Ferrer, the antipope Benedict XIII undertakes, in turn, with the help of the apostate Joshua Ha-Lorki or Geronimo of Santa Fe, his doctor, to proselytize. Although declared schismatic, heretical and perjured by the general council of Pisa, he was, however, recognized as a pope in the Iberian Peninsula, and he hoped to confound his enemies and rise with brilliance in the eyes of Christendom by bringing, by his efforts, the massive conversion of Jews from Spain.(with the help of Ferrer, he organized the dispute over Tortosa). He summoned (at the end of the year 1412) the most learned rabbis and Jewish writers of Aragon to a religious conference in Tortosa. […]. The discussion had been dragging on for sixty days without one of the Jewish representatives seeming yet to be converted. On the contrary, in their convictions they strengthened themselves by the struggle itself. […]

Vincent Ferrer’s offensive

- There were only a small number of converts in the great communities of Saragossa, Calatayud and Daroque, but on the other hand, several small communities, whose existence was threatened by the Christians among whom they were isolated, passed whole to Christianity. All these new converts, the papal court brought them in groups to Tortosa, where they presented themselves together in the hall of seances and made public their profession of faith of Christians. These were living trophies for the Church, and the pope thought that the defenders of Judaism would at last lose their courage and declare themselves defeated. […]

- But the pope was disappointed in his predictions, the Jews did not convert in mass. Except for a few failings, the great communities of Aragon and Catalonia remained steadfast in their faith, and Benedict XIII did not have the joy of presenting himself in triumph, as he had hoped, before the next Council of Constance. […] In his disappointment, he attacked the Talmud and the poor little dose of freedom still enjoyed by the Jews. […]

Pope Martin V

- Fortunately, at that moment, the Pope’s power was almost nil, for while he persecuted the Jews, he was deposed by the Council of Constance, and Vincent Ferrer’s fanatical preachings still robbed him of the last remaining partisans. […] In Portugal, Jews did not have to suffer from Ferrer’s fanaticism.

- The ruler of that country, Don João I had more serious concerns than that of helping to convert Jews, he was preparing to make in Africa the first conquests that marked the beginning of the maritime power of the Portuguese. So, when Ferrer asked permission to come to fight in Portugal the sins of the Christians and the blindness of the Jews, he made him say that he could come, but his head encircled by an incandescent iron crown. Thanks to the tolerance of the king, the Jews of Portugal enjoyed complete security, and many baptized Jews from Spain took refuge in that country. Moreover, Don João I expressly forbade the mistreatment of new converts emigrated to Portugal or their delivery to Spain. But there were many other countries in Europe where Ferrer, either by his sermons or by the reputation of his exploits, caused considerable harm to the Jews. […]

- In the midst of their worries, the Jews suddenly glowed for them a ray of hope. The Council of Constance had just elected Martin V (who, among other things, following the actions of many Jews in Europe, including Spain) promulgated a bull (31 January 1419), which can be considered to some extent as a protest against the measures taken by antipope Benedict XIII. She started like this:

- Since the Jews are made in the image of God and the debris of their nation will one day find salvation, we decree, like our predecessors, that it is forbidden to disturb them in their synagogues, to attack their laws, habits and customs, to baptize them by compulsion, to force them to celebrate the Christian holidays, to impose on them the wearing of new distinctive signs, or to hinder their commercial relations with Christians.

It is this salutary result that the psalmist describes in the sequel of the psalm of this generation:

- All nations surrounded me; in the name of the Lord that I shall cut them off.

- They encircled me, yea they surrounded me; in the name of the Lord that I shall cut them off.

- They encircled me like bees; they were extinguished like a thorn fire; in the name of the Lord that I shall cut them off.

- You pushed me to fall, but the Lord helped me.

- The might and the cutting power of God was my salvation.

The hardening of the Iberian Jews in their faith

In fact, successive attacks by Christians on the Iberian Jewish communities have resulted in many conversions. At first, many of them were sincere and corresponded to an aspiration of some to finally belong to the new Spanish people that was created for a few generations as the progress of the reconquest. Still others considered that Christianity was only an extension of Judaism, which was not incompatible with it. Most of them converted, especially in the hope of avoiding segregation measures, but remained profoundly Jewish in their souls:

- Most conversos [4], entered into Christianity out of ease, opportunism or fear, continue in secret (or hardly in secret) to practice Judaism. Certainly, their child is baptized; but when the ceremony returns, the family practices the rite of « hadas » or « vijola »; the baby is plunged into lustral water, where jewels and fragrant herbs have been soaked, to purify him, and to promise him future fertility. Then, the boy is circumcised. The Hebrew calendar of weeks and holidays continues to be observed. On Friday nights, the kitchen is ready, the lamp is lit, the family dresses in their own clothes and then no longer works on the Sabbath until Saturday evening. The eight lights are ritually lit during the Chanukah feast; the Passover is celebrated, with its special nourishment, like that of Sukkot with its huts of foliage, as are always observed the great fasts of the 9th of Av and Yom Kippur. Funerals are also performed according to the Jewish ritual, and the clerics of the Inquisition who seek the false converts to condemn them « post mortem », by opening the vaults, know recognize the enveloped bodies of the prayer shawl, on the ground , hands resting on the chest. The daily diet is always kosher; a famous converso like Diego Arias Davila of Segovia, always lends his oven to the Jews of the city, because he likes to eat with them; he has remained openly Jewish, everyone knows it in the city, because he will pray with the Jews at the synagogue and join them to complete the minyan (jewish quorum).

This attachment of the Jews in adversity to Judaism who despite appearances continue to venerate at home (« in the tents« ) the precepts of the covenant continue to make them righteous who by their prayers (« singing praises ») continue to to draw their strength and their faith in a favorable future, even if for this last point the next generations will not give them reason.

This is what the psalmist praises in the following of the psalm of this generation:

- A voice of singing praises and salvation is in the tents of the righteous; the right hand of the Lord deals valiantly.

- The right hand of the Lord is exalted; the right hand of the Lord deals valiantly.

- I shall not die but I shall live and tell the deeds of God.

- God has chastised me, but He has not delivered me to death.

In fact, the episode of 1391 allowed the Sephardic Jews to be more ideologically offensive. Although this will not allow them to save their communities a few decades later in the Iberian Peninsula, this combativeness will allow Sephardic Judaism to survive the expulsion of 1492 from Spain and Portugal.

Another Jewish intellectual, converted to Christianity in 1391, then returned to Judaism, and after a stay in the land of Israel, put himself in the front line to defend Judaism against Christian dogmas:

- Furious at the betrayal of Bonet (one of his converted friends who refused to return to Judaism), and certainly aware of the great skill it would take to write an open letter attacking the religious faith newly appreciated by his friend. Duran wrote a missive full of sarcasm and bitterness.

- Duran wrote that his own faith had not wavered since his conversion and that his friend’s rejection of his theological and real Jewish ancestors was a rejection of the Jewish people and Judaism. […]

- On the suggestion of Crescas with whom he was apparently in contact at the time, and encouraged by him, he wrote a subtle anti-Christian polemic text entitled « kelimat ha goyim » (The Shame of the Gentiles) in which he tried to show the accuracy of Judaism.

This reaction of Jewish intellectuals upstream of this generation to the Christian cultural offensive has enabled the Jews of this generation, as seen at the Tortosa dispute and as will be seen in 1492 where a significant number of Jews from to prefer exile to the abandonment of their faith.

The reaffirmation of Jewish thought outside of philosophical influences supported by respect for Jewish law following an established tradition (the Halakha) is the « cornerstone » of the covenant edifice, one that prevents it from becoming crack definitely leading to the disappearance of the Jewish community.

It is this salutary reaction (« gates of righteousness« ) that the psalmist notes in the following of this generation’s psalm:

- Open for me the gates of righteousness; I shall enter them and thank God.

- This is the Lord’s gate; the righteous will enter therein.

- I shall thank You because You answered me, and You were my salvation.

- The stone that the builders rejected became a cornerstone.

- This was from the Lord; it is wondrous in our eyes.

- This is the day that the Lord made; we shall exult and rejoice thereon.

However the psalmist can not afford to conclude on an essentially positive note, it is obvious that if thanks to his attachment to the precepts of the law transmitted by Moses, the Jews as a people will miraculously cross the ages as they did so far and for the next five centuries, many Jews will be the ones who pay for it with their lives or those of their loved ones.

If the psalmist accepts this sacrifice (« Bind the sacrifice« ) he does not fail to recall the divine commitment to the purpose of this one.

This is how he concludes the psalm of this generation:

- Please, O Lord, save now! Please, O Lord, make prosperous now!

- Blessed be he who has come in the name of the Lord; we have blessed you in the name of the Lord.

- The Lord is God, and He gave us light. Bind the sacrifice with ropes until [it is brought to] the corners of the altar.

- You are my God and I shall thank You; the God of my father, and I shall exalt You.

- Give thanks to the Lord because He is good, for His kindness is eternal.

[1] According to: Denis Menjot: « Medieval Spain, 409-1474 ». (French: « Les Espagnes médiévales, 409-1474 ». (p. 210 et 228) )

[2] (directed by) David Biale: « Cultures of the Jews ». Benjamin R. Gampel’s chapter: « Letter to an indocile master – From 1391 to 1498 ». (French: « Les Cultures des Juifs ». Chapitre de Benjamin R. Gampel : « Lettre à un maître indocile – De 1391 à 1498». (p. 401-402) )

[3] Henri Graetz: « HISTORY OF THE JEWS / THIRD PERIOD – DISPERSION ». Second epoch – Science and Jewish poetry at their peak. Chapter XII – Consequences of the persecution of 1391. Marranos and apostates. New Violence – (1391-1420). (Extract from the website: « histoiredesjuifs.com ») (French: « HISTOIRE DES JUIFS / TROISIÈME PÉRIODE — LA DISPERSION ». Deuxième époque — La science et la poésie juive à leur apogée. Chapitre XII — Conséquences de la persécution de 1391. Marranes et apostats. Nouvelles violences — (1391-1420). (Extrait du site web : «histoiredesjuifs.com ») )

[4] Beatrice Leroy: « Jews in Christian Spain before 1492 ». Chapter: « The fate of a religious minority ». (French: « Les Juifs dans l’Espagne chrétienne avant 1492 ». Chapitre : « Le sort d’une minorité religieuse ». (p. 102-103) )