1610 AD to 1630 AD, Psalm 127: The Awakening of Crypto-Jews.

This site was first built in French (see www.147thgeneration.net). The English translation was mainly done using « google translation ». We have tried to correct the result of this translation to avoid interpretation errors. However, it is likely that there are unsatisfactory translations, do not hesitate to communicate them to us for correction.

(for that click on this paragraph)

Summary

This generation of the 1610s and 1620s.

According to our count, this generation is the 127th generation associated with Psalm 127. It is in this Psalm 127 that we therefore find an illustration of the facts of this generation.

Under the background of religious struggle between Catholics and Protestants, this generation saw the beginning of the 30 Years War (1618-1648). The conflict became international in 1621. At the end of the conflict the total population of Germany fell by 30%. The affected Jewish communities, like the rest of the population, are not spared.

Before the Thirty Years War broke out, the city of Amsterdam became the first modern-day Christian city where Jews could practice their religion freely. The Amsterdam government commissioned the illustrious jurist Grotius to study the question of the settlement of the Jews. The Amsterdam magistrate, an Orthodox Calvinist, demanded Jewish orthodoxy. For the first time in history, Jews were given a more enviable status than Christians. Indeed, the Amsterdam magistrate gave Jews the possibility of freely exercising their worship, a possibility which he refused to certain Christian sects.

Talk

The 30 Years War

This generation [1] of the years 1610 and 1620 is marked by the beginning of the war of 30 years which is the culmination of the fight between reform and against reform in Europe and which will especially concern Germany which, although theoretically directed by the emperor , is actually made up of 350 autonomous states.

The conflict began in 1618, when two Catholics were defenestrated in Prague by Protestants who came to complain about the measures concerning them. Although the two defenestrated fare unscathed, the Thirty Years War has just begun. The ruler of Bohemia, of which Prague is a member, had, in 1617, ceased to play the game of confessional and political pluralism, desiring the restoration of Catholicism to the detriment of the Protestants. The Prague event soon leads to a general war. The reasons are numerous: they combine religious motivations (the antagonism between Catholics and Protestants), political (the desire for autonomy in relation to the Habsburgs), and territorial (many princes seek to enlarge their states).

The conflict began in 1618, when two Catholics were defenestrated in Prague by Protestants who came to complain about the measures concerning them. Although the two defenestrated fare unscathed, the Thirty Years War has just begun. The ruler of Bohemia, of which Prague is a member, had, in 1617, ceased to play the game of confessional and political pluralism, desiring the restoration of Catholicism to the detriment of the Protestants. The Prague event soon leads to a general war. The reasons are numerous: they combine religious motivations (the antagonism between Catholics and Protestants), political (the desire for autonomy in relation to the Habsburgs), and territorial (many princes seek to enlarge their states).

Despite the first military successes of the Protestants, Catholics supported by the Pope and the King of Spain won a decisive victory in 1620. This has the effect of internationalizing the conflict and causing in 1621 the resumption of war between Spain and the United Provinces. Denmark, Sweden and France will be involved in the conflict to varying degrees. Armed gangs plague misery in conflict-affected areas. During [2] the conflict (1618-1648), the total population of Germany fell by 30%. The Jewish communities affected in the same way as the rest of the population are not spared.

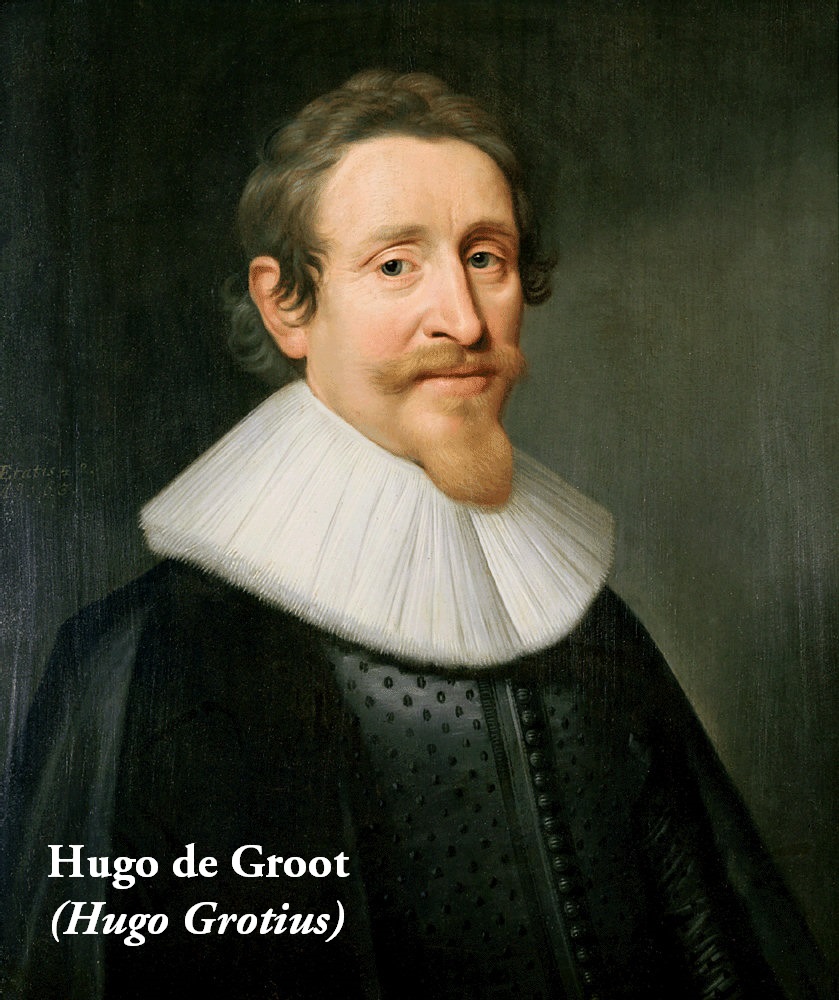

Hugo de Groot (Hugo Grotius)

Before the Thirty Years War broke out, the city of Amsterdam became the first Christian city in modern times where Jews could practice their religion freely.

In 1579 [3], the declaration of Utrecht, founding act of the country stipulates that no one can be worried for his religious opinions. If this declaration was more to ensure the coexistence between Catholics and Protestants than between Jews and Christians, gradually the Jews earn their right of citizenship, right that switches to the present generation:

- The Calvinist clergy [4] did not necessarily see with a particularly favorable eye the official presence of Jews in the Republic (of the United Provinces). Many cities refused to accept them; Alkmaar and Harlem were the first to grant them a charter.

- In Amsterdam, and twice, in 1606 and 1608, they were forbidden to acquire a cemetery. At that time, moreover, and until 1616, the newcomers endeavored to be as discreet as possible, going so far as to use Dutch names in their affairs. Laborious negotiations took place; they ended in 1614. From now on, the Jews of Amsterdam could bury their dead in Ouderkerk, a small locality not far from the city and still keeping the traces of a glorious past.

- But the practice of Judaism was a problem for the magistrate of the city especially as at that time the country was on the verge of a civil war that originated in a theological-political conflict on which were also grafted economic interests.

- The Amsterdam government then commissioned a commission to study the question raised by the settlement of the Jews; among its members, the illustrious jurist Grotius, who presented his conclusions in a report. Inspired by this, the magistrate defines in 1616 the situation of the Jews on the banks of the Amstel. It was « less than an emancipation, but more than a tolerance »: the Jews could not fill any civil or military position, could not proselytise or print works of anti-Christian controversy. On the commercial side, they were excluded from guilds and denied the right to trade at retail.

- On the other hand, an exceptional fact, unique in the history of modern Judaism, not only did no ghetto limit their existence, but the magistrate also made them an obligation to be true Jews. They had to declare that they believed in the law of Moses, the existence of a creator God and his providence, the divine inspiration of Moses and the prophets and the existence of a future life. with penalties for the wicked and rewards for the righteous. The magistrate of Amsterdam, an orthodox Calvinist, a fierce proponent of Gomarus’ theses on predestination, therefore demanded a Jewish orthodoxy in order not to add to the disorders and religious tensions that could arouse heterodoxy, from whence it came. Thus, as early as 1619, the Jews of Amsterdam were forced to observe the strictest observance of their faith. One can imagine the amazement that such a requirement could arouse for the crypto-Jews or conversos who were gaining the city. For the first time in history, Jews were granted a more enviable status than Christians. Indeed, the magistrate of Amsterdam gave Jews the opportunity to freely practice their worship, a possibility he refused to some Christian sects.

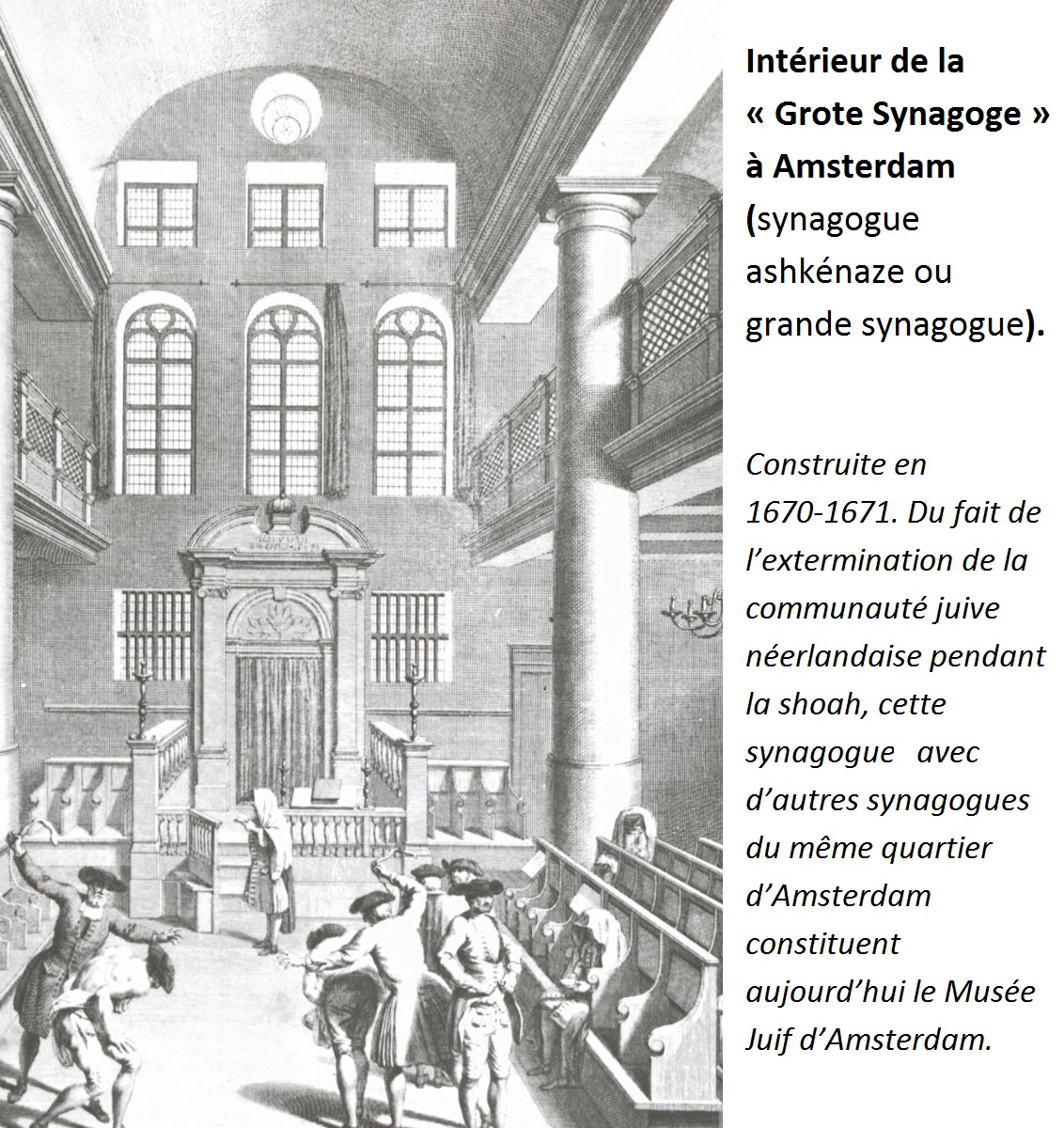

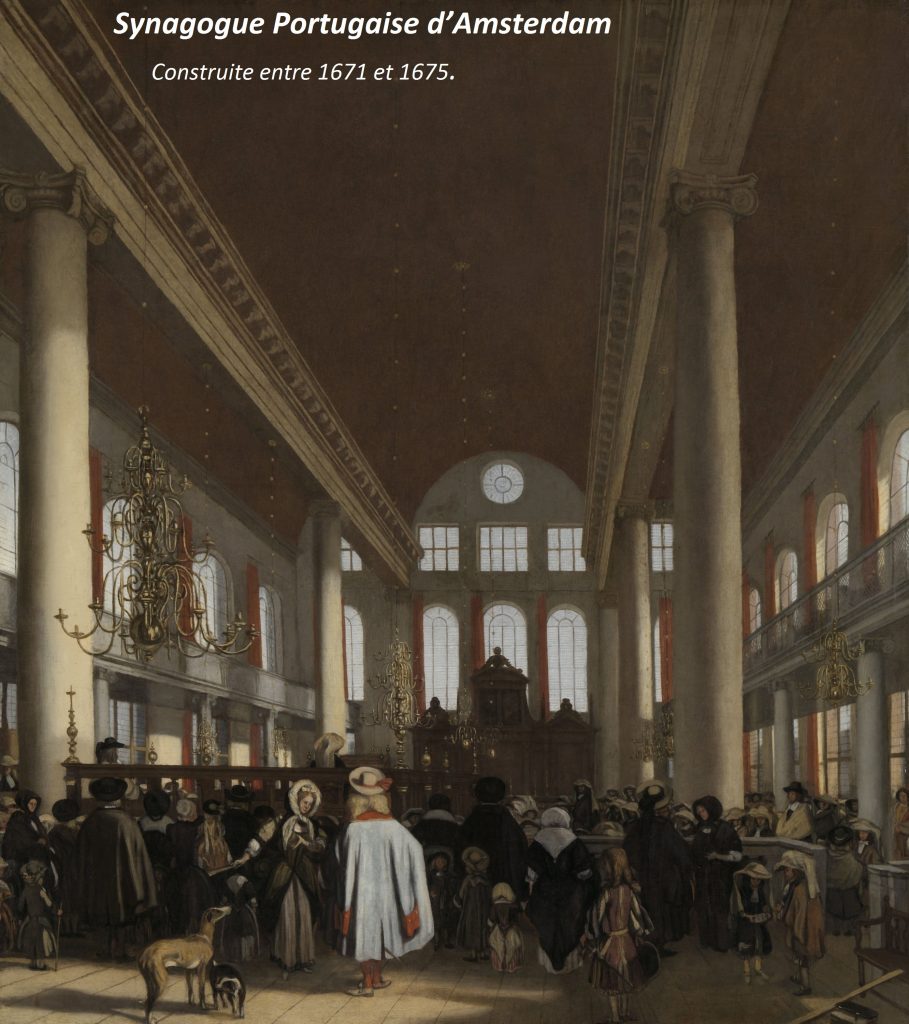

During [5] the truce with Spain, the population growth of the Sephardic population of Amsterdam was remarkable, rising from 500 individuals in 1612 to more than 1,000 in 1620. The Thirty Years’ War ending the truce with Spain stalled for about twenty years the expansion of the Portuguese Jewish community. This slowdown is offset by the arrival of many Ashkenazi Jews fleeing the battlefield.

If we refer to the psalm of this generation, we can note that exceptionally this psalm is written by Solomon, who built the Temple of Jerusalem. It is in this sense that we must interpret the beginning of the psalm of this generation which evokes the house of God, the Temple in Jerusalem and the synagogue since its destruction and the exile of the Jews.

The Jews from Spain who had chosen to keep their religion emigrated to Portugal where they were forced to convert in 1497. Behind a facade of Christianity, many people kept their faith and tried to keep part of the Jewish traditions, in absence of a “house of God”, of synagogues.

More than a century later, the descendants of the converts found refuge in Amsterdam, which many would consider the « new Jerusalem ». Not only can they return to the religion of their fathers but can build their first synagogues that will ensure the rebirth of a real Judaism and its transmission to succeeding generations.

It is this unexpected renaissance that the psalmist evokes in the beginning of the psalm of this generation. Without this divine providence, the efforts of crypto-Jews were doomed to failure:

- A song of ascents about Solomon. If the Lord will not build a house, its builders have toiled at it in vain; if the Lord will not guard a city, [its] watcher keeps his vigil in vain.

- It is futile for you who arise early, who sit late, who eat the bread of toil, so will the Lord give to one who banishes sleep from himself.

Sleep and wakefulness evoke, as we have already seen, the long period of exile (the last two watches of the Jewish night), while the rising represents the final redemption (dawn) of the Jewish people.

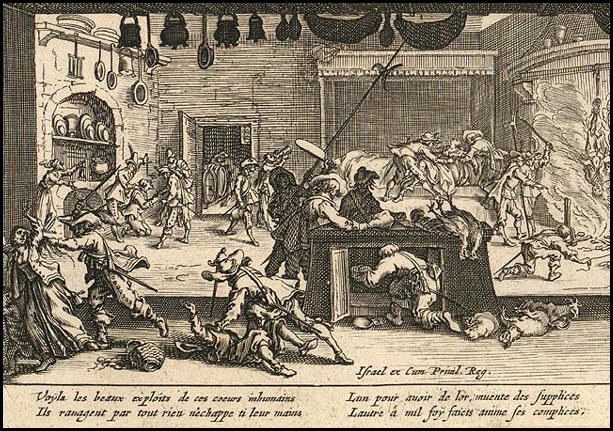

To secretly preserve for over a century the link with the religion of their fathers in the repressive world of the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal, the crypto-Jews have put all their hopes on their descendants:

- How [6] was the marranos tradition passed down from generation to generation? Of course, it could not be a revelation from childhood, until the children had learned to hold their tongue. It was most often done during adolescence, and it seems that the rite of Bar-Mitzvah, or religious maturity, was transformed into a kind of initiation of mystery. Often, the mother was in charge, and in general crypto-Judaism was often perpetuated by women, who will eventually become true priestesses, the « sacerdotisas », the last marranos of the twentieth century.

And also :

- Within [7] the house of a crypto-Jew, the ancestral faith was transmitted with the greatest care, because the most intimate family ties were not always sufficient to ensure secrecy. What father could be absolutely sure of his sons, what son of his father, what wife of her husband, what lovers between them? We know that most of the time, it was up to women to transmit the religion which, little by little, over time, became poorer. To maintain secrecy, endogamy was common. The first cousins often united, and generation after generation, this mode of union was the rule, the women marrying still child, at 12 or 13 years, for a better initiation to the faith of their husband, without fear of indiscretion. And we know that faith a union decided, the marriage was consumed before going to church. The official wedding gave rise to particularly ostentatious festivities which, in the secrecy of the hearths, had to take on a different color: the hated religious oath had been accepted in order to perpetuate an endlessly threatened Jewish life.

It is on this transmission preserved by the descendants that the psalmist concludes the psalm of this generation saluting the abnegation of the Jews of Silence who sacrificed their own lives in the only hope of ensuring the transmission of their faith:

- Behold, the heritage of the Lord is sons, the reward is the fruit of the innards.

- Like arrows in the hand of a mighty man, so are the sons of one’s youth.

- Praiseworthy is the man who has filled his quiver with them; they will not be ashamed when they talk to the enemies in the gate.

[1] According to (directed by) Jean Delumeau: « History of the world from 1492 to 1789 ». Chapter: « The Thirty Years War, 1616-1626 ». (French: « Histoire du monde de 1492 à 1789 ». Chapitre : « La guerre de Trente ans, 1616-1626 ». (p. 222 à 227) ).

[2] According to (directed by) Jean Baumgarten and collective: « A thousand years of Ashkenazi culture ». Chapter of Simon Schwarzfuchs: « The development of Ashkenaz on the threshold of modernity ». (French: « Mille ans de culture ashkénazes ». Chapitre de Simon Schwarzfuchs: « De l’épanouissement d’Ashkenaz au seuil de la modernité ». (p. 80) ).

[3] (directed by) Henri Méchoulan: « The Jews of Spain, history of a diaspora ». Chapter of Yosef Kaplan: « Republic of the United Provinces ». (French: « Les Juifs d’Espagne, histoire d’une diaspora ». Chapitre de Yosef Kaplan: «République des Provinces Unies ». (p. 191) ).

[4] Henry Méchoulan: « To be Jewish in Amsterdam at the time of Spinoza ». Chapter: « Crypto-Jews to the » new Jews of Amsterdam « . (French: « Être Juif à Amsterdam au temps de Spinoza ». Chapitre : « Des Crypto-juifs aux « nouveaux juifs d’Amsterdam ». (p. 24 à 26) )

[5] According to (directed by) Henri Méchoulan: « The Jews of Spain, history of a diaspora ». Chapter of Yosef Kaplan: « Republic of the United Provinces ». (French: « Les Juifs d’Espagne, histoire d’une diaspora ». Chapitre de Yosef Kaplan: «République des Provinces Unies ». (p. 198-199) ).

[6] Léon Poliakov: « History of anti-Semitism ». (French: « Histoire de l’antisémitisme ». (p. 202/203) ).

[7] Henry Méchoulan: « The Jews of silence in the Spanish Golden Age ». (French: « Les Juifs du silence au siècle d’or espagnol ». (p. 73) ).