90 AD to 110 AD, Psalm 52: The Gospels.

This site was first built in French (see www.147thgeneration.net). The English translation was mainly done using « google translation ». We have tried to correct the result of this translation to avoid interpretation errors. However, it is likely that there are unsatisfactory translations, do not hesitate to communicate them to us for correction.

(for that click on this paragraph)

Summary

This generation is from the years 90 AD to 110 AD.

According to our count, this generation is the 52nd generation associated with Psalm 52. It is in this Psalm 52 that we therefore find an illustration of the facts of this generation.

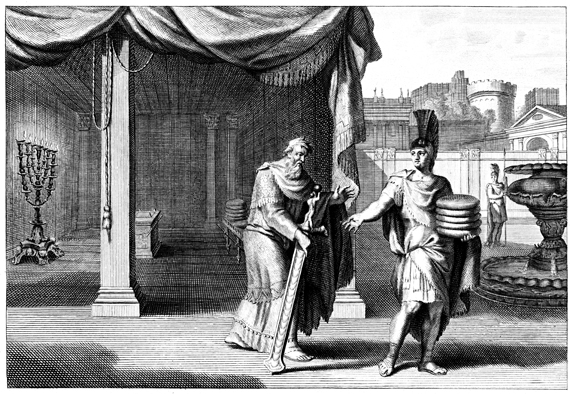

In biblical times, in his flight to escape from Saul’s troops, David found refuge in Nob, where the ark of the covenant and the priests who worship it are. Hungry, he asks to consume the consecrated breads, symbol of worship in the Temple. From this rift in the sacred, Doeg, attempts to completely eradicate the priesthood and the worship of the Temple.

Likewise, after the defeat of 70, Judaism is threatened with death and the sages decided to abolish sacrificial worship and keep the rest of the Mosaic law, in order to preserve the attachment of his people to God through the propagation of the covenant. On this breach in the sacred, the early Christians, as Doeg did with David, try to completely supplant the Jewish people by contesting their election.

Claiming that the sacrificial cult had to be abandoned with the destruction of the temple, they consider that it is the entirety of the law that lapses. It is not surprising that this episode with Doeg is included in the Gospels.

Dating the Gospels is not easy, many Christian scholars tend to set a date as close as possible to the life of Jesus (at least for the canonical Gospels: Gospels of Mark and Matthew). This is to guarantee its authenticity.

It is believed that the first gospel was written in Syria where large numbers of Jews lived. Finally. We can glimpse a controversy against the orthodox Judaism of the Pharisees, as it manifests itself at the synagogical assembly of Jamnia (Yavne) around the years 80 AD. In these conditions, many authors date the first gospel to the 80 AD to AD 90, maybe a little earlier.

For our part we will assume that the Gospel of Matthew was written, and especially, disseminated in the generation that interests us (90/110). Because previously, the synagogal worship of Yavné had not yet arrived at a sufficient maturity to create this rejection reaction by the new Christians (who were then essentially Jews).

The confrontation quoted in the Gospel according to Matthew about the Pharisees, seems to correspond more to the new rules of holiness defined by the school of Yavne which the early Christians refused. This opposition to the Jews, as competitors of the moment and not as contemporaries of Jesus, is even stronger in the other Gospels.

What is only a religious struggle for the triumph of ideas in the generation that interests us will unfortunately serve as a breeding ground for the stubborn rooting of Christian anti-Semitism throughout the centuries that follow. This will obviously be dramatic for the Jewish people who will live in Christian lands. Christianity will not only be a religious force but will also be a political force that will face all Western Jewish communities for nearly twenty centuries.

Talk

Consecrated bread

At the level of the Roman Empire, this generation is marked by the continuation of the reign of Domitian (81/96 brother of Titus who reigned from 79 to 81, and therefore son of Vespasian who preceded them from 69 to 79), followed by the first Antoninus: Marcus Nerva (96/98) still followed the beginning of reign of Trajan (98/117).

Again, it is important to reframe the title of this psalm before trying to understand the scope of the psalm itself.

- For the conductor, a maskil of David.

- When Doeg the Edomite came and told Saul and said to him, « David came to the house of Ahimelech. »

In his flight to escape from Saul’s troops, David found refuge in Nob, where the ark of the covenant and the priests who worship it are. Hungry, he asks to consume the consecrated breads.

- And[1] he arose and went away; and Jonathan came to the city.

- And David came to Nob, to Ahimelech the priest, and Ahimelech came trembling toward David, and said, « Why are you alone, and no one with you? »

- And David said to Ahimelech the priest, « The king charged me with a matter, and said to me, ‘Let no man know anything concerning the matter upon which I am sending you, and with which I have charged you.’ And I troubled the young men (to advance) to a hidden, secret place.

- And now, what is there in your possession? Five loaves of bread? Give them into my hand, or whatever is found. »

- And the priest answered David, and said, « There is no ordinary bread in my possession, but there is holy bread, if the young men have but kept themselves from women. »

Priest Ahimelech accepts David’s request. Doeg, who witnessed the scene with Ahimelech, warns Saul, who then decides to take revenge on the priests who assisted David in his pursuit. But the servants of Saul refused to execute the priests.

Saul then turns to Doeg, who executes the priests:

- And[2] the king said to Doeg, « You turn, and fall upon the priests. » And Doeg turned, and he fell upon the priests, and slew on that day eighty-five men, wearers of the linen ephod.

- And Nob, the city of the priests, he smote with the sharp edge of the sword, both man and woman, infant and suckling, and ox and ass, and lamb, with the sharp edge of the sword.

- And one son of Ahimelech the son of Ahitub, whose name was Abiathar, escaped and fled after David.

The breach of the sacred

This episode perfectly illustrates the generation that interests us.

David who is the bearer of the Messiah lineage is faced with a dilemma: threatened with death and therefore the future Messiah and consequently the people of Israel (or at least his hope of redemption), he must, to survive to disregard the sanctity of the consecrated loaves of worship in the Temple.

He and the priests make the decision to privilege the survival of Israel to the sanctity of the consecrated bread. From this event, Doeg, the Idumen, therefore descending from Esau and symbol of Rome, intervenes to try to completely eradicate the priesthood and worship of the Temple. His effort will be vain because it will survive thanks to Ebiatar who escapes the massacre.

In the generation that interests us, after the defeat of 70, Judaism is threatened with death and the sages, under the leadership of Yohanan ben Zakkai, decide to abolish the sacrificial cult and retain the rest of the mosaic law in order to preserve the attachment of his people to God through the spread of the covenant.

In this breach, the first Christians try, as Doeg did with David, to completely supplant the Jewish people by challenging his election.

Claiming that the sacrificial cult had to be abandoned with the destruction of the temple, they consider that it is the entirety of the law that lapses. It is not surprising that this episode with Doeg is included in the Gospels.

If Jesus was able to cite this episode to open the door to the Gentiles, the writers of the Gospels a few generations later use it to close the door to the Jews: Thus this episode concerning King David is taken up again in Matthew’s Gospel ( also included in the Gospels of Mark and Luke):

- At[3] that time Jesus went thro

- ugh the grainfields on the Sabbath. His disciples were hungry and began to pick some heads of grain and eat them.

- When the Pharisees saw this, they said to him, “Look! Your disciples are doing what is unlawful on the Sabbath.”

- He answered, “Haven’t you read what David did when he and his companions were hungry?

- He entered the house of God, and he and his companions ate the consecrated bread—which was not lawful for them to do, but only for the priests.

- Or haven’t you read in the Law that the priests on Sabbath duty in the temple desecrate the Sabbath and yet are innocent?

- I tell you that something greater than the temple is here.

- If you had known what these words mean, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice,’[a] you would not have condemned the innocent.

- For the Son of Man is Lord of the Sabbath.”

The writing of the Gospels

Dating the Gospels is not easy, many Christian scholars tend to set a date as close as possible to the life of Jesus (at least for the canonical Gospels: Gospels of Mark and Matthew). This is to guarantee its authenticity.

However, we will retain a dating more distant, precisely in the generation that interests us:

- For[4] the old fathers (of the church), the thing was simple: the first gospel had been written by the Apostle Matthew “for believers from Judaism” (Origen). Many still think so, although modern criticism is more attentive to the complexity of the problem. Several factors make it possible to locate the first gospel. It seems clear that the current text reflects Aramaic or Hebrew traditions: typically Palestinian vocabulary (binding and loosening, yoke to wear, reign of heaven …) expressions that Matthew considers it useless to explain to his readers, various uses ( 5.23, 12.5, 23.5.15.23). On the other hand, it does not seem to be the simple translation of an Aramaic original, but to testify to a Greek writing. Although typically steeped in Jewish tradition, it can not be said to be of Palestinian origin. Ordinarily, it is thought that it was written in Syria, perhaps in Antioch (Ignatius refers to it at the beginning of the second century) or in Phenicia, because in these countries lived a large number of Jews. Finally, we can see a controversy against the Orthodox Judaism of the Pharisees, as it manifests itself at the synagogal assembly of Jamnia (Yavne) in the 80s. In these conditions, many authors date the first gospel of the years 80-90, perhaps a little earlier; we can not reach complete certainty on the subject.

For our part we will assume that the Gospel of Matthew was written, and especially, disseminated in the generation that interests us (90/110) because previously, the synagogal worship of Yavné had not yet arrived at a sufficient maturity to create this rejection reaction by the new Christians (who were then essentially Jews).

Faced with the emptiness left by the destruction of the temple and the disappearance of sacrificial worship, there are obviously two tendencies in Palestinian Judaism (and its dependencies):

The split

The coexistence between these two visions quickly becomes impossible.

On the Christian side, the writing of the Gospels is not content with the narration of the life of Jesus; it takes the opportunity to shoot red ball on the competitive cult symbolized by the school of Yavne and thus consumes the separation of the Christian side.

On the Jewish side, it is the same. However, the domination of Christianity in history since its break with Judaism has meant that few traces have come to us from this rupture on the Jewish side. Because, among other things, the good use of censorship throughout the centuries.

The split had already come to light during the destruction of the Temple:

- The[5] Judeo-Christians had disassociated themselves from other Jews during the great Jewish revolt against the Romans of 66. They had preferred to flee to Pella in Transjordan rather than to remain fighting in Jerusalem. In addition, their messianic claims in the person of Jesus clashed with the more material aspirations of the Sages in this time of crisis. The time was not for messianic speculations but for the national reconstruction of Jewish society. The belief in the messiahship of Jesus, even in his divine filiation, must certainly have been badly perceived by the Sages at this time of troubles. It was no longer a question of dissociation from the enemy, or even of conceptions against the course imposed by events, but rather of doctrinal divisions that could have consequences for the whole of Jewish society. In this climate of rallying around a single authority, we could not afford to tolerate groups that split apart. The main fear of the Sages was the influence that Judeo-Christians might have on other members of Jewish society. It should be remembered that at that time nothing differentiated a Jew from a Judeo-Christian. Both attended the synagogue and observed the ritual observances of Judaism. Thus, in this climate of daily contact, one can only assume doctrinal influencing factors, the very ones against which the Sages intended to fight. […]

- The Sages accepted the Judeo-Christians as long as they were not seen as different but as full Jews. That is to say until the 70s / 80s of the 1st century. It was only then, with the Birkat ha-minim (prayer against heretics which seems to particularly target Judeo-Christians called min – minim in the plural -) that the Sages’ gaze towards them changed, and this, irremediably.

So on the Christian side, the following confrontation cited in the Gospel according to Matthew about the Pharisees, seems more adapted to the new rules of holiness defined by the school of Yavné to which the first Christians refuse:

- Then[6] some Pharisees and teachers of the law came to Jesus from Jerusalem and asked,

- “Why do your disciples break the tradition of the elders (not the written law but the oral law)? They don’t wash their hands before they eat!” (…) (Jesus then replies to them)

- Jesus called the crowd to him and said, “Listen and understand. 11 What goes into someone’s mouth does not defile them, but what comes out of their mouth, that is what defiles them.”

This opposition to the Jews, as competitors of the moment and not as contemporaries of Jesus (for that refer especially to Chapter 23 of the Gospel according to Matthew) is affirmed even stronger in the other Gospels:

- Where[7] begins to manifest in the history of the nascent Church a state of mind hostile to the Jews? It is necessary to find the origin back quite high. He was born as soon as Christian preaching turned away from Israel, where it recorded more setbacks than successes, to the Gentiles and found in them compensation for its initial setbacks. It is amplified when the later expansion of Christianity has become the practice of preachers born in paganism, and the Church is no longer essentially, on the sidelines of the Jewish people stiffened in its refusal, but the redeemed kindness. Absent from the epistles of Paul, disappointed by his compatriots, but incapable of hating them, he is clearly manifested in the Fourth Gospel, where the very name of the Jew takes on a pejorative meaning. Christian anti-Semitism is first and foremost the expression of the frustration aroused by Israel’s resistance. It accompanies the pretensions of the nascent Church to supplant the chosen people. It also translates the need to explain the refusal of the Jews to the message intended for them.

The roots of anti-Semitism

What is only a religious struggle for the triumph of ideas in the generation that interests us will unfortunately serve as a breeding ground for the stubborn rooting of Christian anti-Semitism throughout the centuries that follow.

This will obviously be dramatic for the Jewish people who will live in Christian lands. Christianity will not only be a religious force but will also be a political force that will face all Western Jewish communities for nearly twenty centuries.

It is this danger that David tells us in the psalm of this generation that sees the beginning of the writing of the Gospels or at least their dissemination. These could have been limited to using Jesus to bring the pagans to the divine faith. They go further by trying at the same time to designate the new Christian people as the « true Israel » which is a harbinger of many dramas for the Jewish people:

- Why do you boast of evil, you mighty man? God’s kindness is constant.

- Your tongue plots destruction, as a sharpened razor, working deceit.

- The writers of the Gospels by introducing the arguments of their own struggle prepare a future that is both fatal for the Jewish people and for the world by distorting the divine message of its original significance.

- You loved evil more than good, falsehood more than speaking righteousness forever.

- You loved all destructive words, a deceitful tongue.

- In wanting to bring down the « Jewish competition » of this generation, the authors will generate much more harm than desired,

- God, too, shall tear you down forever; He will break you and pluck you from [your] tent, and uproot you from the land of the living forever.

- David recalls the final fate of the house of Esau which will eventually have to recognize the supremacy, at least vis-à-vis God of Jacob,

- And righteous men will see and fear, and laugh at him.

- « Behold the man who does not place his strength in God and trusts his great wealth; he strengthened himself in his wickedness. »

- Christianity throughout the centuries that follow will not be content to be a spiritual power, all the empires of the West will be under its control. It is this power that will be constantly used towards the Jewish communities of Christian empires.

The wild olive tree

So David is fond of reminding Christians that what Jesus himself had announced and that Paul had confirmed: if the people of Israel can seem to be forgotten by their God in the eyes of other peoples, the night is not made to last and dawn will dawn.

So says Paul:

- If some[8] of the branches have been broken off, and you, though a wild olive shoot, have been grafted in among the others and now share in the nourishing sap from the olive root,

- do not consider yourself to be superior to those other branches. If you do, consider this: You do not support the root, but the root supports you.

- You will say then, “Branches were broken off so that I could be grafted in.”

- Granted. But they were broken off because of unbelief, and you stand by faith. Do not be arrogant, but tremble.

- For if God did not spare the natural branches, he will not spare you either.

- Consider therefore the kindness and sternness of God: sternness to those who fell, but kindness to you, provided that you continue in his kindness. Otherwise, you also will be cut off.

- And if they do not persist in unbelief, they will be grafted in, for God is able to graft them in again.

- After all, if you were cut out of an olive tree that is wild by nature, and contrary to nature were grafted into a cultivated olive tree, how much more readily will these, the natural branches, be grafted into their own olive tree!

It is by taking up this image that David concludes this psalm by modulating some of Paul’s speech: the natural branches (the Jewish people) have not been cut off from the olive tree (I am like a fresh olive tree in the house of God), if the pagans can be grafted to the olive tree it will not be at the expense of the people of Israel:

- But I am like a fresh olive tree in the house of God; I have trusted in the kindness of God forever and ever.

- I will thank You forever and ever when You have done [this], and I will hope for Your name, for it is good, in the presence of Your devoted ones.

[1] Shmuel I – I Samuel – Chapter 21, verses 1 to 5

[2] Shmuel I – I Samuel – Chapter 22, verses 18 to 20

[3] Matthew, Chapter 12, verses 1 to 8

[4] New Testament / Complete Edition TOB / Stag Publishing / Introduction to the Gospel according to St. Matthew. (French reference: Nouveau Testament/édition intégrale TOB/Éditions du Cerf/Introduction à l’évangile selon Saint-Matthieu ).

[5] Dan Jaffé / Judaism and the advent of Christianity / General introduction (french reference : Dan Jaffé/Le judaïsme et l’avènement du christianisme/Introduction générale (pages 39/40 et 78) )

[6] Matthew, Chapter 15, verses 1,2 and 10

[7] Marcel Simon: “Verus Israel” / Chapter “The conflict of orthodoxies / Christian anti-Semitism” (French reference: “Verus Israel”/Chapitre « Le conflit des orthodoxies/L’antisémitisme Chrétien » (II, page 245) ).

[8] Romans 11 ( New International Version (NIV) ), Chapter 11, verses 19 to 24.