1530 AD to 1550 AD, Psalm 123: Safed.

This site was first built in French (see www.147thgeneration.net). The English translation was mainly done using « google translation ». We have tried to correct the result of this translation to avoid interpretation errors. However, it is likely that there are unsatisfactory translations, do not hesitate to communicate them to us for correction.

(for that click on this paragraph)

Summary

This generation of the 1530s and 1540s.

According to our count, this generation is the 123rd generation associated with Psalm 123. It is in this Psalm 123 that we therefore find an illustration of the facts of this generation.

This generation is seeing an increase in the Jewish population in the Holy Land, so the Jewish community in Jerusalem continues to grow. But the city’s overall growth makes the Jewish population a minority. The expansion of the Jewish presence in Jerusalem, if confirmed, remains constrained by the Ottoman administration and the economic situation.

The weak economic outlets of the city and the competition of colonization practiced by the Muslims and the Christians limit the possibilities of implantation of the Jews. Those who wish to make their “aliyah” without giving up their love for the Holy City find a fallback solution by investing the city of Safed. The city will thus bring together many scholars of the time who will revive interest in Kabbalah in particular (following the impetus, among others, of Isaac Louria).

In this generation, the Spanish and Portuguese are taking full advantage of the riches of the Americas discovered simultaneously with the expulsion of the Jews. It sounds like a divine reward. Thus the extension of the Inquisition to Portugal in 1536, now affects Jews who were forcibly converted, unlike the first Spanish Inquisition which only affected Jews who had chosen the choice of conversion (even if their choices were limited).

Talk

Aliyah is speeding up

To this generation of the 1530s and 1540s, the Jewish population in the Holy Land is expanding, so the Jewish community of Jerusalem continues to grow. But the overall growth of the city makes the Jewish population a minority. The expansion of the Jewish presence in Jerusalem, if confirmed, remains constrained by the Ottoman administration and the economic situation.

Despite the precarious economic situation, the religious life is affirmed:

- But [1] it is especially twenty years after the journey of Bassola (in 1522) that religious life reaches its peak. Several prominent rabbinical scholars mark the Jewish community of Jerusalem in the middle of the century. The life of each of them is characteristic of both the renewal of Jerusalem and the difficulties that arise.

- Levi Ben Habib (1483-1545) suffered all the tribulations of the expulsion from Spain, including the forced baptism in Portugal. […] Some time in Safed, to raise himself in holiness, he decided to settle in Jerusalem, probably around 1536. Of the holy city, he fights with energy against the religious predominance of Safed. […]. (This rivalry between the two cities) proves that two important centers exist in rivalry with each other in this sixteenth century: Jerusalem and Safed. The prestige of Jerusalem remains finally intact. It is also enhanced by other personalities than Levi Ben Habib.

Conscious of the limits of settlement in Jerusalem, because of the weak economic opportunities of the city and the competition of colonization practiced by the Muslims and the Christians, the Jews wishing to make their « aliyah », without giving up their love for the City holy find a fallback solution by investing the city of Safed:

- If there exists [2] a city (of the Holy Land) to which the term « Renaissance » obviously applies, it is Safed in the 16th century. The city exists not since Biblical times, but since the Talmudic period. […]

- On the eve of the Ottoman conquest, Safed and its environs have just under seven hundred and fifty heads of Muslim families and about three hundred Jewish heads of families. After the Ottoman conquest and the arrival of the expelled from Spain, the number of Jews increased considerably. It multiplies by five, while the Muslim population multiplies by two. No Christian lives in Safed at this time. In a 1555 tax census, there are more Jewish families than Muslim families. (..) In total about fifteen thousand souls, of whom more than half are Jewish. […]

- The feelings of hostility towards the Jews, so marked in Jerusalem in past centuries, have not had the opportunity to develop in Safed, and Jews, from the end of the fifteenth century, are welcomed with much more kindness than in Jerusalem. The economic development of the city under the Ottomans encouraged local leaders to attract a Jewish population, known to have generally good professional qualities, especially when their families came from Spain. No doubt the city does not have the prestige of Jerusalem. But this lack is partially offset by the proximity of the tomb of the prestigious R. Simon Bar Yohai to Meron, considered the father of Kabbalist tradition. Other tombs of great sages of the Talmudic period are also found in Galilee (where Safed is located). […]

- (Other reasons justify this gathering of Jews in Safed: the Messianic hope – the Messiah must appear in Galilee -, the climate of Safed is more favorable than in Jerusalem, the economy is more flourishing thanks to textiles among others ).

- All these elements make it possible to understand that Safed could have been in the sixteenth century, even more than Jerusalem, at the center of an extraordinary activity that was both economic and spiritual. […]

- It is between 1535 and 1555 that several very important rabbinic personalities come to settle in Safed.

Safed and Kabbalah

Safed will bring together many scholars of the time who will revive interest in Kabbalah (following the impetus of Isaac Louria among others):

- It is in Safed [3] that the Kabbalah of the sixteenth century reaches its peak. Joseph Caro, Solomon Halevi Alkabets, Moses Cordovero (1522-1570) are among the most prominent Kabbalists in the city; they clearly benefit from the gathering of various schools of Jewish mysticism which operates there. Isaac Louria Ashkenazi (1534-1572) created the famous school of which Haim Vital (1542-1620), his disciple, developed and popularized the system to exert a profound influence on the Sephardic and Ashkenazi Kabbalists of the following centuries.

The influence of these scholars in Safed also concerns the Jewish liturgy:

- Solomon [4] Alkabets Halevi (1505-1584) arrived at Safed in 1536, at the same time as Joseph Caro. His influence is considerable and his pupils numerous. However, he is especially famous for his liturgical poem « Lékah Dodi » in honor of the Sabbath, where his name appears in acrostiche. Steeped in deep mysticism but made accessible by the allegory of « Shabbat fiancee » hosted by her fiance Israel, the poem celebrates Shabbat both in its temporal significance and in its messianic drive. In a few short years and thanks to printing, this poem is spreading, with minimal variations, in Jewish communities around the world. It becomes a fundamental part of the Friday night prayers for the Sabbath welcome. His poetic strength but also the prestige of Erets Israel have made the poem, composed to Safed by Akabets, the most popular postbiblical texts of the ritual of prayers.

In this poem, the author reaffirms his confidence in God and reaffirms his belief in the coming of the Messiah who will put an end to the humiliations suffered by the Jews by other peoples (the expulsion from Spain is still in everyone’s minds especially some who lived it).

Thus the revival of Judaism, including its mystical component infused by the Jewish communities of Jerusalem and Safed, make it possible to turn the page of the expulsion from Spain by turning resolutely towards the future without ignoring the persistent difficulties of exile.

This is what the beginning of the Psalm of this generation expresses:

- A song of ascents. To You I lifted up my eyes, You Who dwell in heaven.

- Behold, as the eyes of slaves to the hand of their masters, as the eyes of a handmaid to the hand of her mistress, so are our eyes to the Lord our God, until He favors us.

- Favor us, O Lord, favor us, for we are fully sated with contempt.

The pursuit of the Inquisition

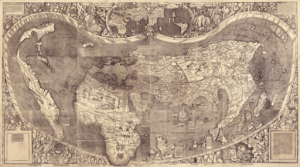

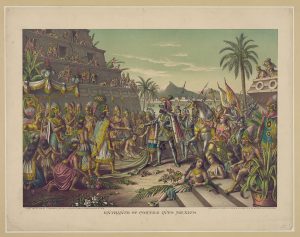

While Christoph Columbus had limited his establishment in the West Indies, in 1519 Cortes discovers South America and begins the conquest from the current Mexico, the Portuguese had their foot in Brazil as early as 1500 (thinking to discover a new archipelago) which in a mysteriously timely manner had fallen into their possession following the Treaty of Tordesillas which in 1494 decided to divide the world between Spain and Portugal with the Pope’s blessing. Other European countries are not left out, Jacques Cartier discovers Canada in 1537 without visibly realizing the importance of the continent discovered (North America).

The hegemony of Spain and Portugal on the new world will be questioned only later, while waiting for the gold and the riches of the new world abound in the Iberian peninsula comforting the monarchs of these countries that the decision of to expel the Jews from their kingdom has been beneficial to them and has brought them the divine blessing. This blessing, however, will not be eternal, and soon these countries will disappear from the front of the European stage and the international scene.

For the generation that interests us it is not yet the case, gold and other riches of the Americas flock to Spain and Portugal.

In Spain, the Jews officially disappeared in 1492, those who remained necessarily converted, sometimes sincerely, sometimes with the hope of being able to return to the Jewish religion after the storm passed. The inquisition persecutes them in the first decades after the expulsion in order to keep only sincere new Christians.

In our generation, Spain could consider having gotten rid of its Jews, including crypto-Jews. Soon, she will look into the fate of the new Christians (Jews sincerely converted to Christianity). Portugal had pronounced the expulsion of its Jews in 1497, leaving at first a certain freedom to the Jews accepting the conversion, guaranteeing them of any inquiry into the reality of their conversion for twenty years. However, the commitments, when they concern the Jews and that they are favorable to them are rarely definitive and rather quickly the crypto-Jews Portuguese take refuge in the clandestinity.

Simultaneously with the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, Spain discovered a new world. In the generation that interests us, Spain and Portugal perceive fabulous riches from this new world, even if they are illusory and will probably contribute to the drift of these countries in future generations.

This seeming prosperity seems to reward the efforts of these countries in their defense of Christianity, in their efforts to make definitive disappear Judaism, implanted for more than a millennium, their lands. With the extension of the Inquisition to Portugal in 1536, it will now affect converts by force unlike the first Spanish inquisition that affected only Jews who had chosen the choice of conversion (although the possibilities of choices were restricted).

This culminating point of the fate of the Jews in Iberian soil justifies the end of the psalm of this generation:

- Our soul is fully sated with the ridicule of the complacent, the contempt [shown] to the valley of doves.

[1] Renée Neher-Bernheim: « Jewish Life in the Holy Land, 1517-1918 ». Chapter: « The sixteenth century ». (French: «La vie juive en Terre sainte, 1517-1918». Chapitre : « Le XVIe siècle ». (p. 50/51) )

[2] Renée Neher-Bernheim: « Jewish Life in the Holy Land, 1517-1918 ». Chapter: « The sixteenth century ». (French: «La vie juive en Terre sainte, 1517-1918». Chapitre : « Le XVIe siècle ». (p. 53/58) )

[3] Esther Benbassa and Aron Rodrigue: « History of the Sephardic Jews ». Chapter: « Economy and Culture ». (French: « Histoire des Juifs sépharades ». Chapitre : « Économie et culture ». (p. 161) )

[4] Renée Neher-Bernheim: « Jewish Life in the Holy Land, 1517-1918 ». Chapter: « The sixteenth century ». (French: «La vie juive en Terre sainte, 1517-1918». Chapitre : « Le XVIe siècle ». (p. 60) )